Difference between revisions of "deLemus"

| Line 167: | Line 167: | ||

2. Put all ref info here, use only name tag in text for easier management | 2. Put all ref info here, use only name tag in text for easier management | ||

3. Comment tag of no use instead of removing | 3. Comment tag of no use instead of removing | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

<ref name=":0">Harvey, W. T. ''et al.'' SARS-CoV-2 variants, Spike mutations and immune escape. ''Nat Rev Microbiol'' '''19,''' 409–424 (2021).</ref> | <ref name=":0">Harvey, W. T. ''et al.'' SARS-CoV-2 variants, Spike mutations and immune escape. ''Nat Rev Microbiol'' '''19,''' 409–424 (2021).</ref> | ||

<ref name=":2">Li, B. et al. Identification of Potential Binding Sites of Sialic Acids on the RBD Domain of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. ''Front Chem.'' '''9''', 659764 (2021)</ref> | <ref name=":2">Li, B. et al. Identification of Potential Binding Sites of Sialic Acids on the RBD Domain of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. ''Front Chem.'' '''9''', 659764 (2021)</ref> | ||

| Line 178: | Line 177: | ||

<ref name="CellRep20220517">Westendorf, K. ''et al.'' LY-CoV1404 (bebtelovimab) potently neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 variants. ''Cell Rep'' '''39,''' 110812 (2022).</ref> | <ref name="CellRep20220517">Westendorf, K. ''et al.'' LY-CoV1404 (bebtelovimab) potently neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 variants. ''Cell Rep'' '''39,''' 110812 (2022).</ref> | ||

<ref name="COVID Data Tracker">COVID Data Tracker: Variant Proportion https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions (2023).</ref> | <ref name="COVID Data Tracker">COVID Data Tracker: Variant Proportion https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions (2023).</ref> | ||

| − | |||

<ref name="Donzelli">Donzelli, S. ''et al.'' Evidence of a SARS-CoV-2 double spike mutation D614G/S939F potentially affecting immune response of infected subjects. ''Comput Struct Biotechnol J'' '''20,''' 733–744 (2022).</ref> | <ref name="Donzelli">Donzelli, S. ''et al.'' Evidence of a SARS-CoV-2 double spike mutation D614G/S939F potentially affecting immune response of infected subjects. ''Comput Struct Biotechnol J'' '''20,''' 733–744 (2022).</ref> | ||

<ref name="Gaebler">Gaebler, C. ''et al.'' Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. ''Nature'' '''591,''' 639–644 (2021).</ref> | <ref name="Gaebler">Gaebler, C. ''et al.'' Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. ''Nature'' '''591,''' 639–644 (2021).</ref> | ||

| Line 188: | Line 186: | ||

<ref name="Sun_Glycobio2021">Sun, X.-L. The role of cell surface sialic acids for SARS-CoV-2 infection. ''Glycobiology'' '''31,''' 1245–1253 (2021).</ref> | <ref name="Sun_Glycobio2021">Sun, X.-L. The role of cell surface sialic acids for SARS-CoV-2 infection. ''Glycobiology'' '''31,''' 1245–1253 (2021).</ref> | ||

<ref name="Tian_2009">Tian, S. A 20 residues motif delineates the furin cleavage site and its physical properties may influence viral fusion. ''Biochem Insights'' '''2,''' (2009).</ref> | <ref name="Tian_2009">Tian, S. A 20 residues motif delineates the furin cleavage site and its physical properties may influence viral fusion. ''Biochem Insights'' '''2,''' (2009).</ref> | ||

| − | |||

<ref name="VanBlargan2022">VanBlargan, L. A. ''et al.'' An infectious SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 omicron virus escapes neutralization by therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. ''Nat Med'' '''28,''' 490–495 (2022).</ref> | <ref name="VanBlargan2022">VanBlargan, L. A. ''et al.'' An infectious SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 omicron virus escapes neutralization by therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. ''Nat Med'' '''28,''' 490–495 (2022).</ref> | ||

<ref name="Wang_JMedVirol2022">Wang, Q. ''et al''. Key Mutations on Spike Protein Altering ACE2 Receptor Utilization and Potentially Expanding Host Range of Emerging SARS‐CoV‐2 Variants. ''J Med Virol.'' '''95''', 1-11 (2022).</ref> | <ref name="Wang_JMedVirol2022">Wang, Q. ''et al''. Key Mutations on Spike Protein Altering ACE2 Receptor Utilization and Potentially Expanding Host Range of Emerging SARS‐CoV‐2 Variants. ''J Med Virol.'' '''95''', 1-11 (2022).</ref> | ||

| Line 201: | Line 198: | ||

--> | --> | ||

| + | <ref name="Tegally">Tegally, H. ''et al.'' Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 omicron lineages BA.4 and BA.5 in South Africa. ''Nat Med'' '''28,''' 1785–1790 (2022).</ref> | ||

| + | <ref name="Del Rio">Del Rio, C. & Malani, P. N. COVID-19 in 2022 - The Beginning of the End or the End of the Beginning? ''JAMA'' '''327''', 2389–2390 (2022).</ref> | ||

<ref name="Aggarwal">Aggarwal, A. ''et al''. Mechanistic Insights into the Effects of Key Mutations on SARS-CoV-2 RBD–ACE2 Binding. ''Phys Chem Chem Phys'' '''23''', 26451–26458 (2021)</ref> | <ref name="Aggarwal">Aggarwal, A. ''et al''. Mechanistic Insights into the Effects of Key Mutations on SARS-CoV-2 RBD–ACE2 Binding. ''Phys Chem Chem Phys'' '''23''', 26451–26458 (2021)</ref> | ||

<ref name="Callaway">Callaway, E. What Omicron’s BA.4 and BA.5 variants mean for the pandemic. ''Nature'' '''606''', 848–849 (2022).</ref> | <ref name="Callaway">Callaway, E. What Omicron’s BA.4 and BA.5 variants mean for the pandemic. ''Nature'' '''606''', 848–849 (2022).</ref> | ||

Revision as of 17:54, 7 February 2023

Dynamic Expedition of Leading Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein

Spike Glycoprotein

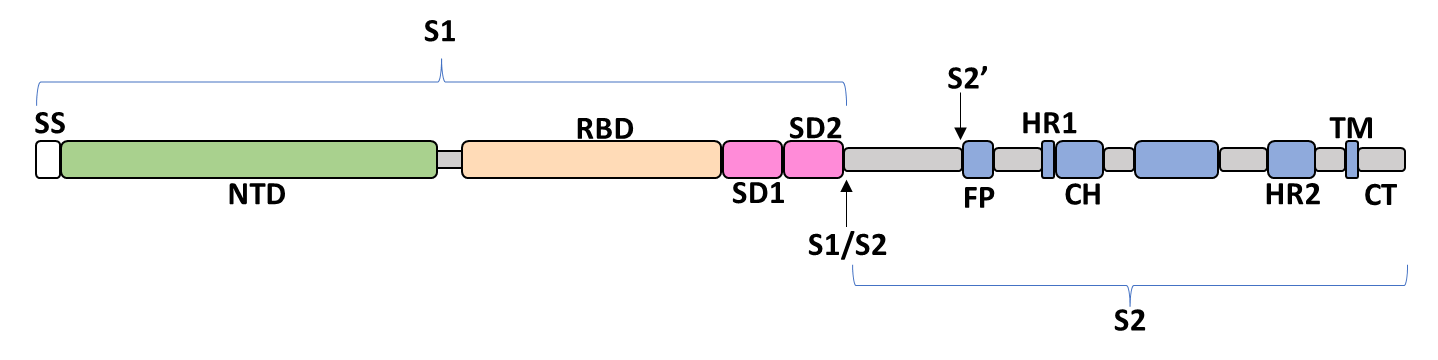

The spike glycoprotein of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a trimeric type I viral fusion protein that binds the virus to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor of a host cell.[1] It is composed of 2 subunits: the N-terminal subunit 1 (S1) and C-terminal subunit 2 (S2), within which multiple domains lie. The S1 region facilitates ACE2 binding and is made up of an N-terminal domain (NTD ~ 1 – 325), a receptor-binding domain (RBD ~ 326 – 525), and 2 C-terminal subdomains (CTD1 and CTD2 ~ 526 – 688), while the downstream S2 region is responsible for mediating virus-host cell membrane fusion.

Update (03/02/2023)

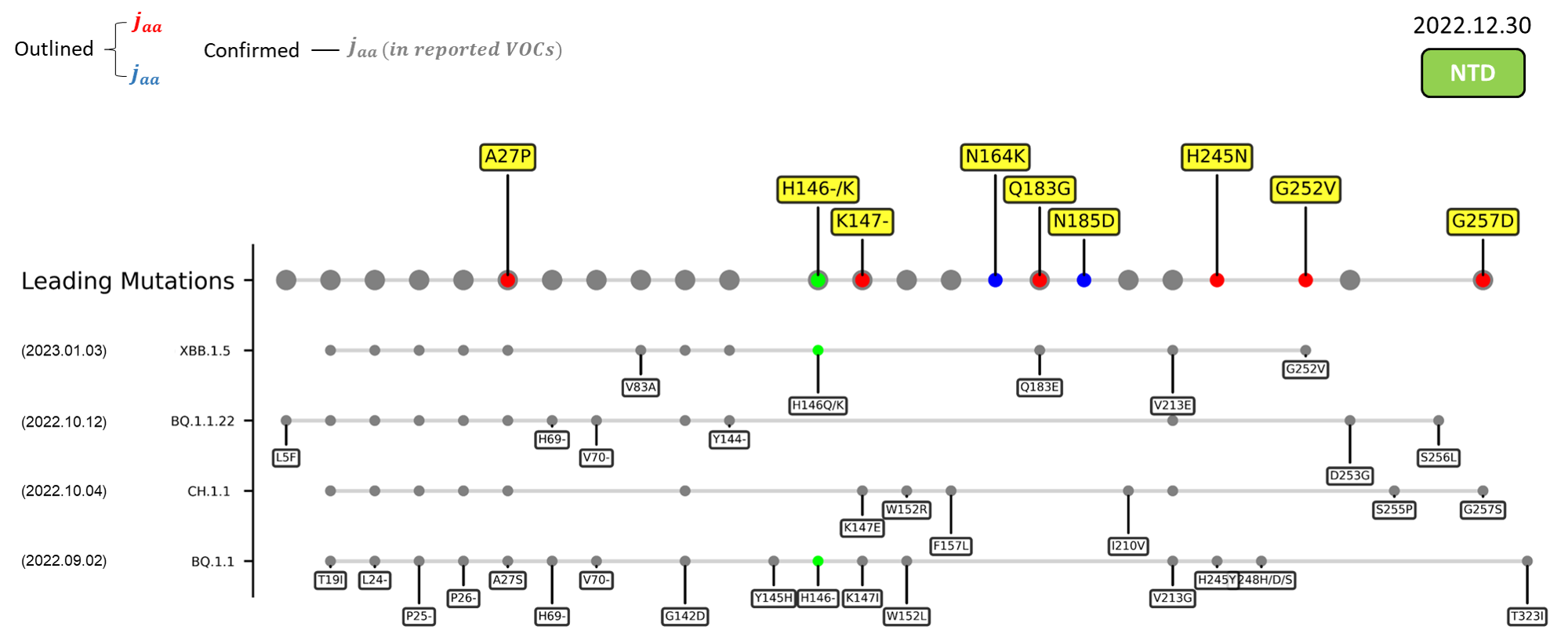

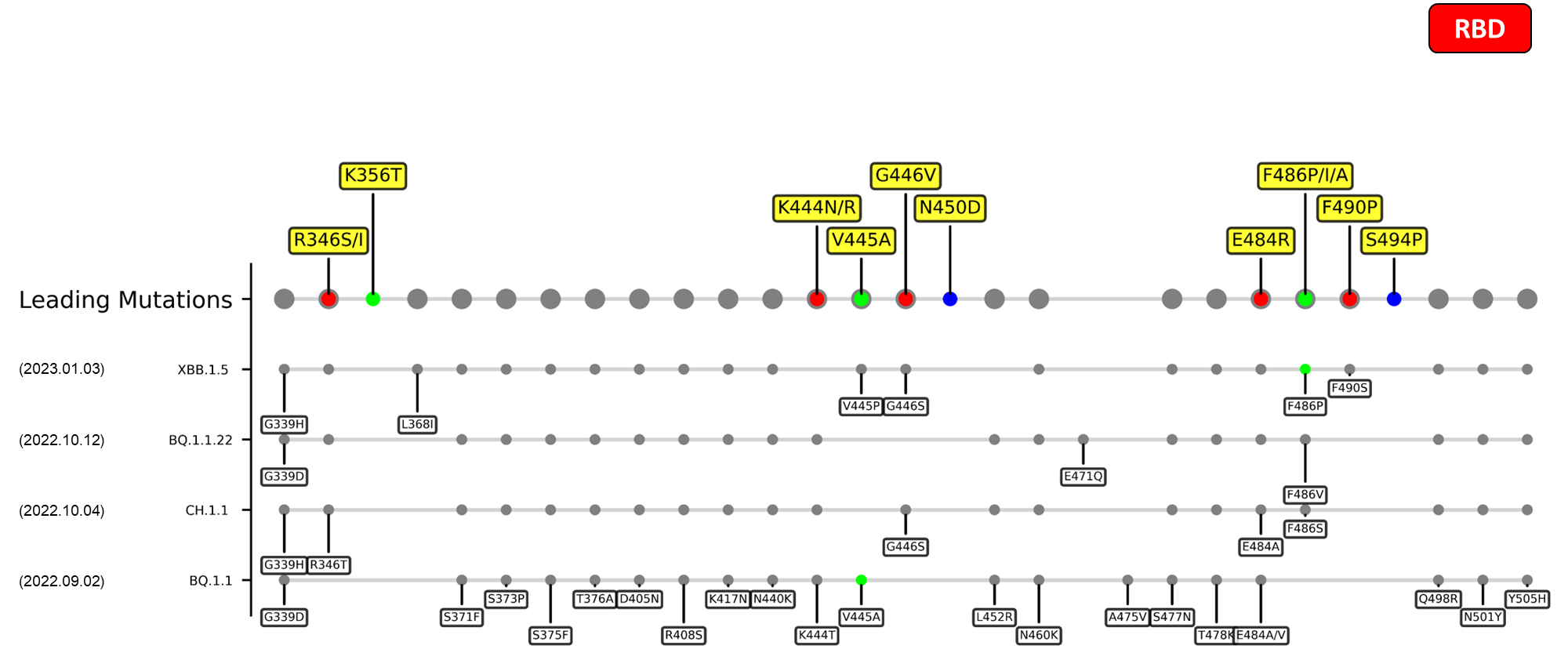

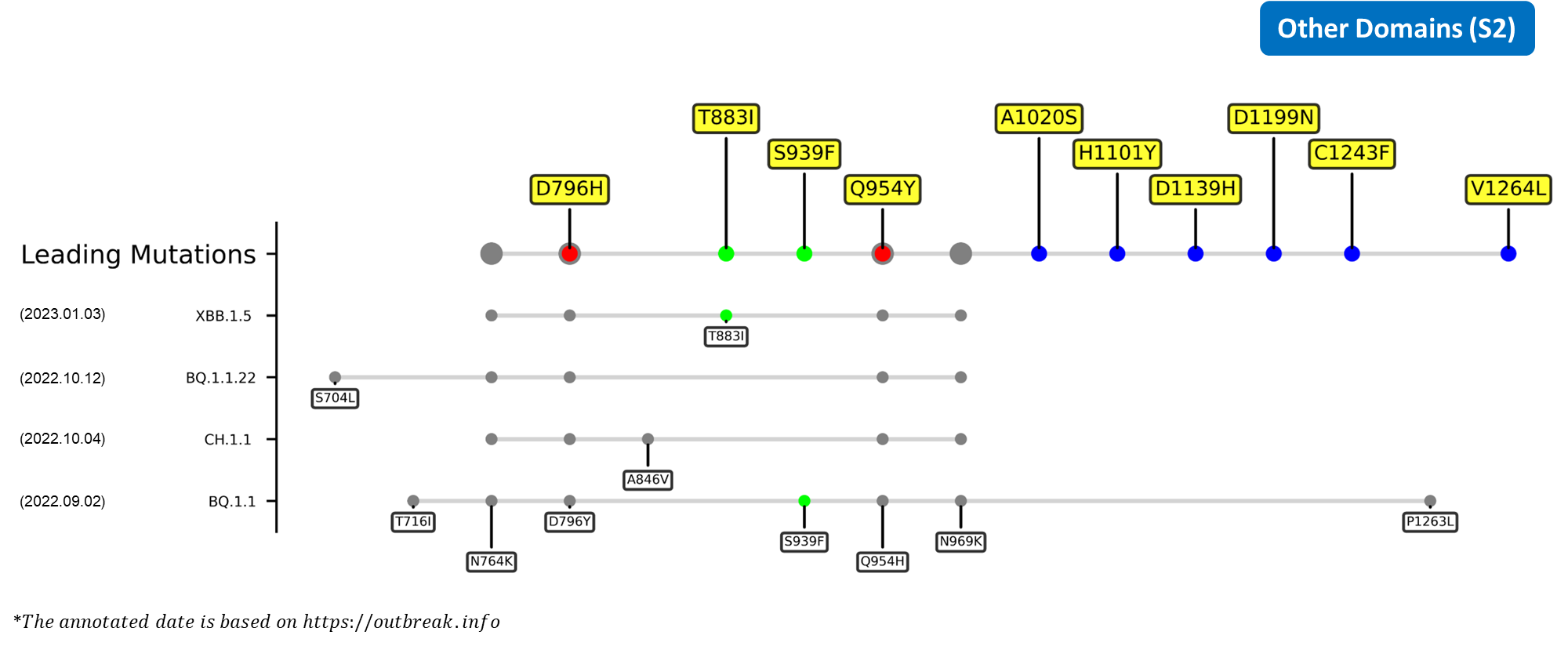

The recently confirmed leading mutations are listed as follows.

2023.01.31

| Outlined Mutations | Confirmed in VOC/Emerging Variants |

|---|---|

| V445A | BQ.1.1 |

2023.01.17 - 2023.01.25

| Outlined Mutations | Confirmed in VOC/Emerging Variants |

|---|---|

| H146-/K | BQ.1.1, XBB.1.5 |

| E583D | BQ.1.1 |

| Q613H | BQ.1.1 |

| S939F | BQ.1.1 |

Summary

The constantly shifting epidemiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) ever since its initial outbreak has been a result of the continuous evolution of its etiological agent, SARS-CoV-2, from which numerous variants have been generated. Even within the first 2 years of this pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) has already announced 4 variants of concern (VOC), which are the previously circulating alpha (B.1.1.7), beta (B.1.351), gamma (P.1), and delta (B.1.617.2) strains, and many other variants of interest (VOI). The successive emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants has brought along many novel mutations, most of which continually refine and improve the fitness of the virus. For instance, these functionally advantageous mutations include the N501Y of alpha and L452R and E484Q of the B.1.617 lineage, which are capable of enhancing the ACE2-binding affinity of the spike glycoprotein.[2]

The latest SARS-CoV-2 lineage to be designated the status of VOC would be omicron (B.1.1.529) which first originated from South Africa.[3] This particular lineage alone has undergone substantial evolution over the course of its global dominance, spreading across the world like wildfire while simultaneously producing a diverse soup of dissimilar subvariants.[4] The first of its kind would be the BA.1 strain first appeared in November 2022. The supremacy of BA.1, however, would not last long, forasmuch as the emergence of the more fit BA.2 strain in December 2022 would eventually outcompete its antecedent.[5] Few months later, between March and July 2022, the successive emergences of BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5, and BA.2.75 would once again garnered the attention of the WHO and multiple countries. For one, the BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5 subvariants were found to possess enhanced antibody evasion capabilities and transmissibility when compared to the formerly active BA.2 strain,[4][6][7] allowing them to become dominant in the US and the UK.[8][9]BA.2.75, on the other hand, was the dominant variant in India, which habors higher hACE2-binding affinity than the BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants.[10][11] The complex interactions between these omicron sublineages prompted the creations of even more novel strains, including the recombinant XBB subvariant derived from BA.2.10.1 and BA.2.75 in August 2022, and the BQ.1 subvariant derived from BA.5 in October 2022. Like their predecessors, XBB swiftly rose to prominence upon its emergence, which was then succeeded by BQ.1 up till the end of 2022.[12][13] In fact, BQ.1.1, a descendent of BQ.1, was found to be the culprit behind 36.3% of the total US reported COVID-19 cases in December 2022.[14]

Recent emerging variant (EV) data retrieved from GISAID, as of 17 January 2023, has revealed that the top 4 most rapidly spreading lineages are the BA.1.1.22, CH.1.1, XBB.1.5, and BQ.1.1 variants, among which XBB.1.5 has been found to be especially prevalent in the US, making up of more than 40% of its sequence coverage in early January 2023.[14] The identified leading mutations are listed as follows:

References

- ↑ Jackson, C. B., Farzan, M., Chen, B. & Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 23, 3–20 (2021).

- ↑ Aggarwal, A. et al. Mechanistic Insights into the Effects of Key Mutations on SARS-CoV-2 RBD–ACE2 Binding. Phys Chem Chem Phys 23, 26451–26458 (2021)

- ↑ Karim, S. S. A. & Karim, Q. A. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: A new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398, 2126–2128 (2021).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Tegally, H. et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 omicron lineages BA.4 and BA.5 in South Africa. Nat Med 28, 1785–1790 (2022).

- ↑ Yamasoba, D. et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2 spike. Cell 185, 2103-2115.e19 (2022).

- ↑ Cao, Y. et al. BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 escape antibodies elicited by Omicron Infection. Nature 608, 593–602 (2022).

- ↑ Wang, Q. et al. Antibody evasion by SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5. Nature 608, 603–608 (2022).

- ↑ Callaway, E. What Omicron’s BA.4 and BA.5 variants mean for the pandemic. Nature 606, 848–849 (2022).

- ↑ Del Rio, C. & Malani, P. N. COVID-19 in 2022 - The Beginning of the End or the End of the Beginning? JAMA 327, 2389–2390 (2022).

- ↑ Cao, Y. et al. Characterization of the enhanced infectivity and antibody evasion of Omicron BA.2.75. Cell Host Microbe 30, (2022).

- ↑ Shaheen, N. et al. Could the New BA.2.75 Sub-Variant Cause the Emergence of a Global Epidemic of COVID-19? A Scoping Review. Infect Drug Resist 15, 6317–6330 (2022).

- ↑ Wang, Q. et al. Alarming antibody evasion properties of rising SARS-CoV-2 BQ and XBB subvariants. Cell 186, (2023).

- ↑ European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Spread of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant sub-lineage BQ.1 in the EU/EEA https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Epi-update-BQ1.pdf (2022).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Highly immune evasive omicron XBB.1.5 variant is quickly becoming dominant in U.S. as it doubles weekly https://www.cnbc.com/2022/12/30/covid-news-omicron-xbbpoint1point5-is-highly-immune-evasive-and-binds-better-to-cells.html (2023).

Structure Testing