Difference between revisions of "deLemus"

m (→Summary) |

m (→Summary) |

||

| Line 141: | Line 141: | ||

--> | --> | ||

==Summary== | ==Summary== | ||

| − | The dynamic epidemiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) since its outbreak has been a result of the continuous evolution of its etiological agent, SARS-CoV-2. Within the first 2 years of this pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) has already announced 4 variants of concern (VOC), namely alpha (B.1.1.7), beta (B.1.351), gamma (P.1), and delta (B.1.617.2), together with numerous variants of interest (VOI). The latest lineage to be designated a VOC would be omicron (B.1.1.529),<ref name="Karim" /> from which a diverse variant soup is generated.<ref>Callaway, E. COVID ‘variant soup’ is making winter surges hard to predict. ''Nature'' '''611,''' 213–214 (2022).</ref> From the BA.1 strain of November 2021 to the BQ.1 strain of October 2022,<ref name="Wang" /><ref name="European Centre" /> each omicron subvariant has successively proliferated and outcompeted its once dominant antecedent.<ref name="Del Rio" /> The emergence of all these variants has assuredly brought along many novel mutations that | + | The dynamic epidemiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) since its outbreak has been a result of the continuous evolution of its etiological agent, SARS-CoV-2. Within the first 2 years of this pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) has already announced 4 variants of concern (VOC), namely alpha (B.1.1.7), beta (B.1.351), gamma (P.1), and delta (B.1.617.2), together with numerous variants of interest (VOI). The latest lineage to be designated a VOC would be omicron (B.1.1.529),<ref name="Karim" /> from which a diverse variant soup is generated.<ref>Callaway, E. COVID ‘variant soup’ is making winter surges hard to predict. ''Nature'' '''611,''' 213–214 (2022).</ref> From the BA.1 strain of November 2021 to the BQ.1 strain of October 2022,<ref name="Wang" /><ref name="European Centre" /> each omicron subvariant has successively proliferated and outcompeted its once dominant antecedent.<ref name="Del Rio" /> The emergence of all these variants has assuredly brought along many novel mutations that continue to fine-tune the fitness of the virus,<ref>Carabelli, A. M. ''et al.'' SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: Immune escape, transmission and fitness. ''Nat Rev Microbiol'' (2023).</ref> leading to its persistent global circulation. |

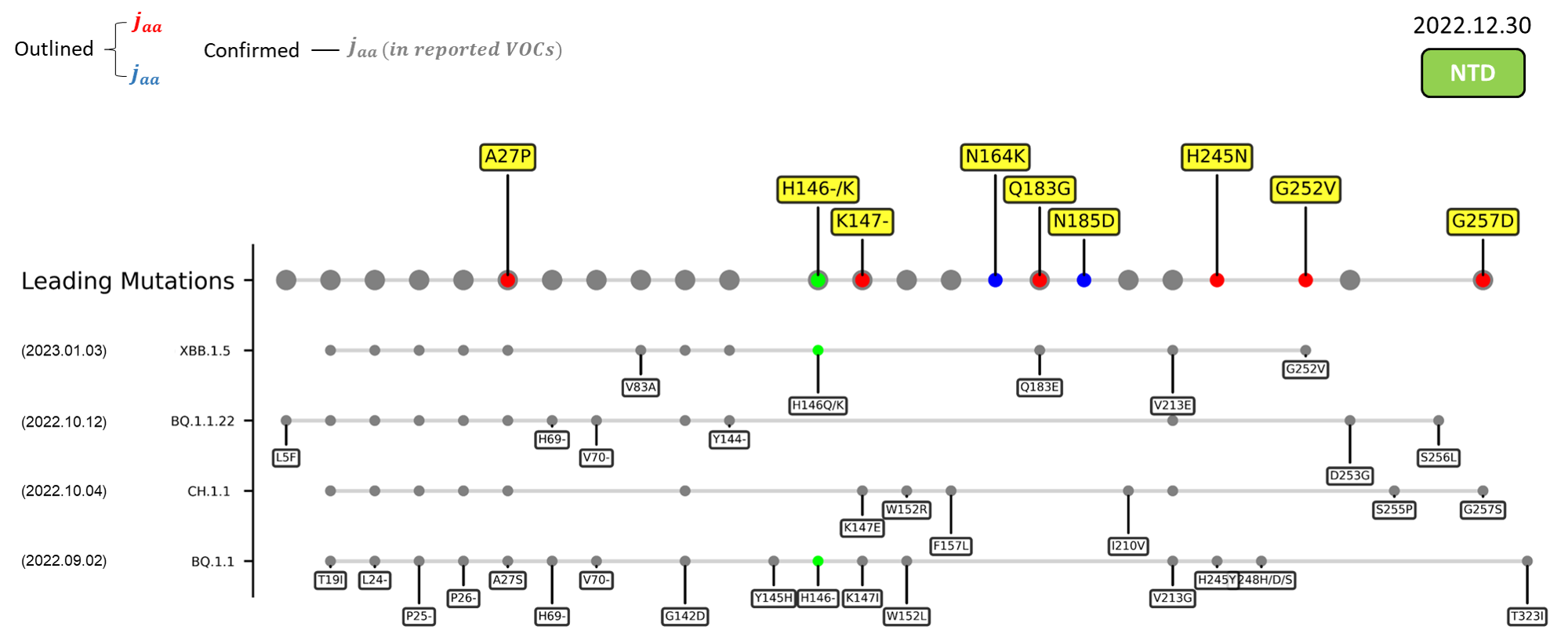

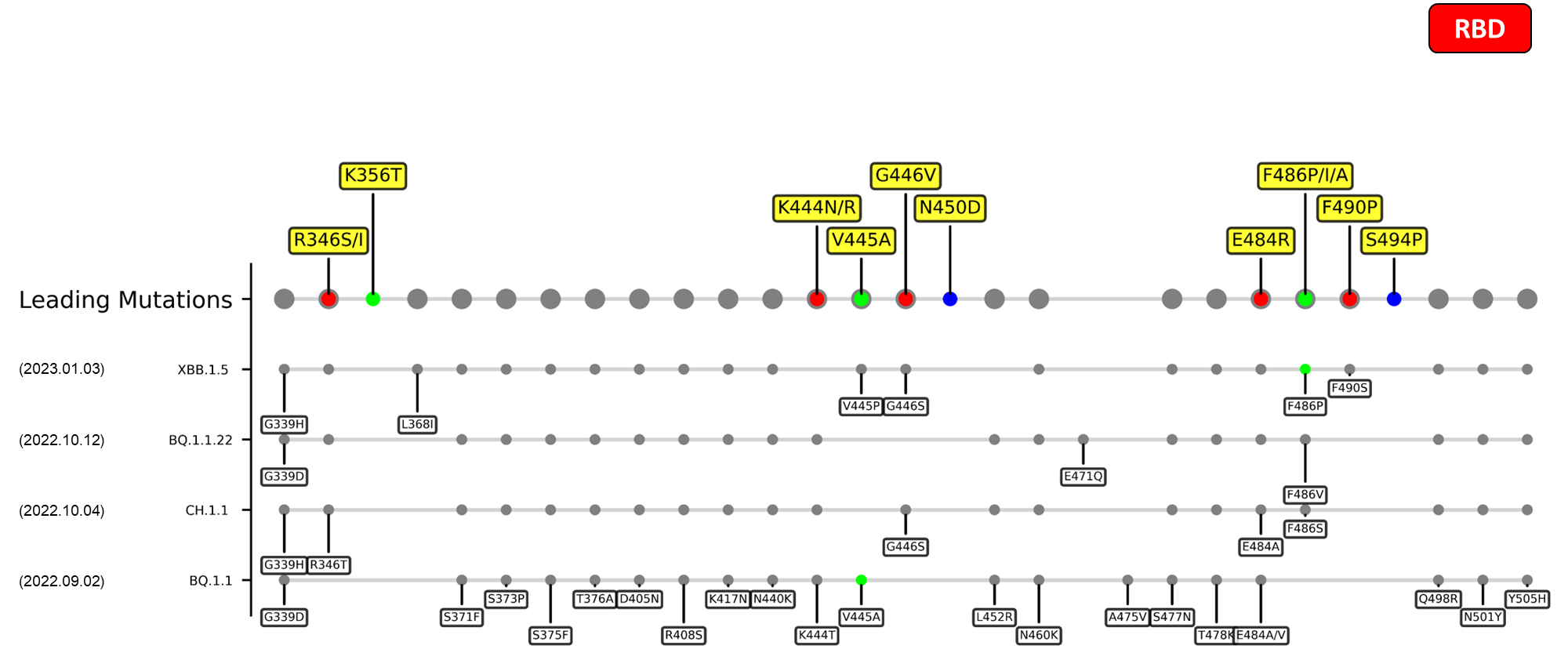

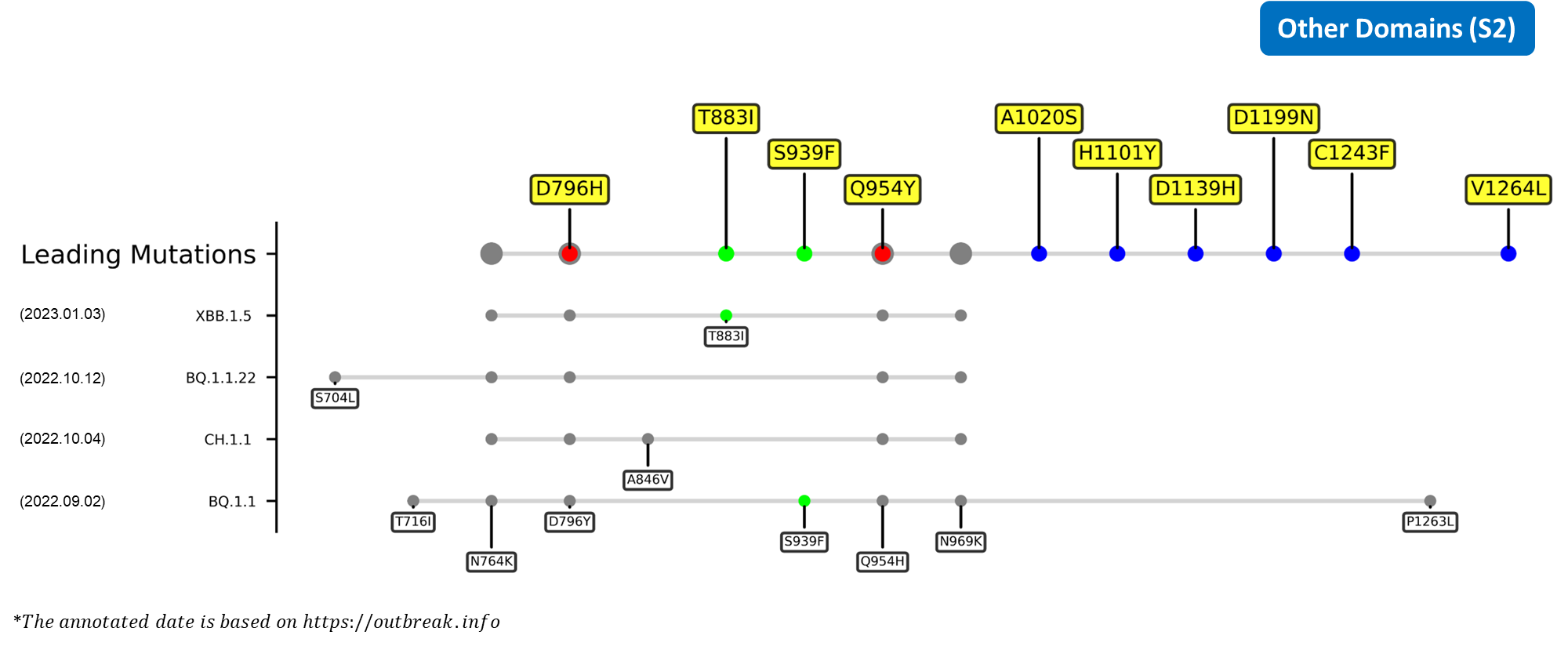

Recent emerging variant (EV) data retrieved from GISAID, as of 17 January 2023, has revealed that the top 4 most rapidly spreading lineages are the BA.1.1.22, CH.1.1, XBB.1.5, and BQ.1.1 variants, among which XBB.1.5 has been found to be especially prevalent in the US, making up of more than 40% of its sequence coverage in early January 2023.<ref name="CNBC XBB.1.5" /> The identified leading mutations are listed as follows: | Recent emerging variant (EV) data retrieved from GISAID, as of 17 January 2023, has revealed that the top 4 most rapidly spreading lineages are the BA.1.1.22, CH.1.1, XBB.1.5, and BQ.1.1 variants, among which XBB.1.5 has been found to be especially prevalent in the US, making up of more than 40% of its sequence coverage in early January 2023.<ref name="CNBC XBB.1.5" /> The identified leading mutations are listed as follows: | ||

Revision as of 05:15, 8 February 2023

Dynamic Expedition of Leading Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein

Spike Glycoprotein

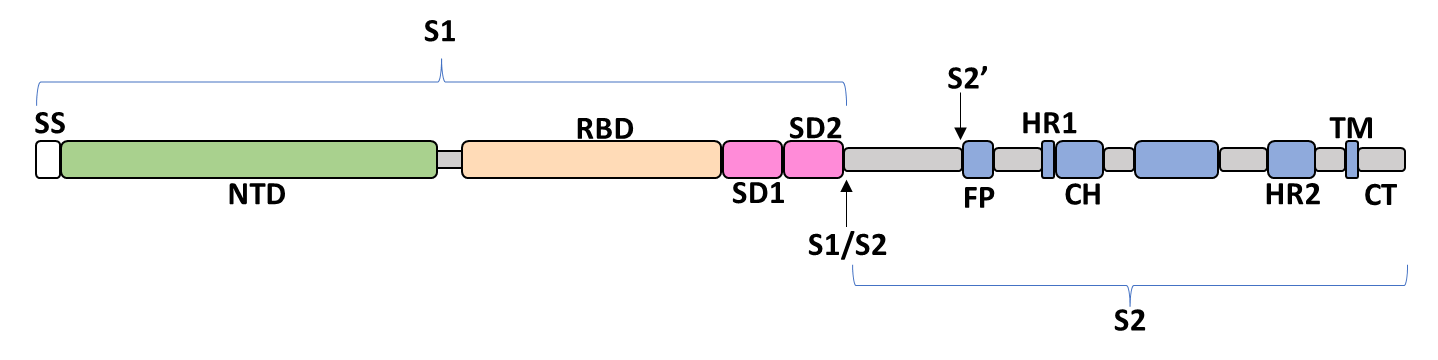

The spike glycoprotein of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a trimeric type I viral fusion protein that binds the virus to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor of a host cell.[1] It is composed of 2 subunits: the N-terminal subunit 1 (S1) and C-terminal subunit 2 (S2), within which multiple domains lie. The S1 region facilitates ACE2 binding and is made up of an N-terminal domain (NTD ~ 1 – 325), a receptor-binding domain (RBD ~ 326 – 525), and 2 C-terminal subdomains (CTD1 and CTD2 ~ 526 – 688), while the downstream S2 region is responsible for mediating virus-host cell membrane fusion.

Update (03/02/2023)

The recently confirmed leading mutations are listed as follows.

2023.01.31

| Outlined Mutations | Confirmed in VOC/Emerging Variants |

|---|---|

| V445A | BQ.1.1 |

2023.01.17 - 2023.01.25

| Outlined Mutations | Confirmed in VOC/Emerging Variants |

|---|---|

| H146-/K | BQ.1.1, XBB.1.5 |

| E583D | BQ.1.1 |

| Q613H | BQ.1.1 |

| S939F | BQ.1.1 |

Summary

The dynamic epidemiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) since its outbreak has been a result of the continuous evolution of its etiological agent, SARS-CoV-2. Within the first 2 years of this pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) has already announced 4 variants of concern (VOC), namely alpha (B.1.1.7), beta (B.1.351), gamma (P.1), and delta (B.1.617.2), together with numerous variants of interest (VOI). The latest lineage to be designated a VOC would be omicron (B.1.1.529),[2] from which a diverse variant soup is generated.[3] From the BA.1 strain of November 2021 to the BQ.1 strain of October 2022,[4][5] each omicron subvariant has successively proliferated and outcompeted its once dominant antecedent.[6] The emergence of all these variants has assuredly brought along many novel mutations that continue to fine-tune the fitness of the virus,[7] leading to its persistent global circulation.

Recent emerging variant (EV) data retrieved from GISAID, as of 17 January 2023, has revealed that the top 4 most rapidly spreading lineages are the BA.1.1.22, CH.1.1, XBB.1.5, and BQ.1.1 variants, among which XBB.1.5 has been found to be especially prevalent in the US, making up of more than 40% of its sequence coverage in early January 2023.[8] The identified leading mutations are listed as follows:

References

- ↑ Jackson, C. B., Farzan, M., Chen, B. & Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 23, 3–20 (2021).

- ↑ Karim, S. S. A. & Karim, Q. A. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: A new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398, 2126–2128 (2021).

- ↑ Callaway, E. COVID ‘variant soup’ is making winter surges hard to predict. Nature 611, 213–214 (2022).

- ↑ Wang, Q. et al. Alarming antibody evasion properties of rising SARS-CoV-2 BQ and XBB subvariants. Cell 186, (2023).

- ↑ European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Spread of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant sub-lineage BQ.1 in the EU/EEA https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Epi-update-BQ1.pdf (2022).

- ↑ Del Rio, C. & Malani, P. N. COVID-19 in 2022 - The Beginning of the End or the End of the Beginning? JAMA 327, 2389–2390 (2022).

- ↑ Carabelli, A. M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: Immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat Rev Microbiol (2023).

- ↑ Highly immune evasive omicron XBB.1.5 variant is quickly becoming dominant in U.S. as it doubles weekly https://www.cnbc.com/2022/12/30/covid-news-omicron-xbbpoint1point5-is-highly-immune-evasive-and-binds-better-to-cells.html (2023).