Difference between revisions of "deLemus"

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

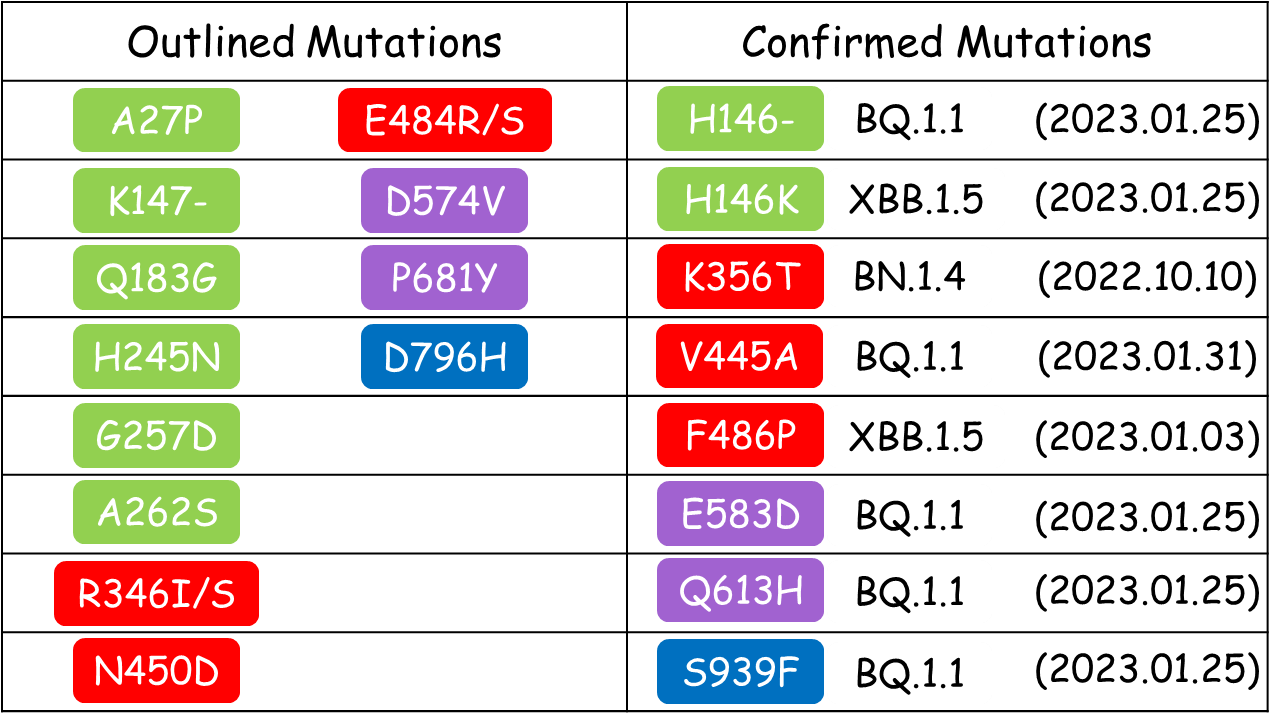

<big>Other mutations that were outlined by our deLemus analysis in December 2022, and were subsequently identified as new emerging mutations carried by the top 4 most rapidly spreading lineages according to the latest data retrieved from GISAID (2023.01.25), are listed as follows:</big> | <big>Other mutations that were outlined by our deLemus analysis in December 2022, and were subsequently identified as new emerging mutations carried by the top 4 most rapidly spreading lineages according to the latest data retrieved from GISAID (2023.01.25), are listed as follows:</big> | ||

| − | <htmltag tagname="img" src="https://wiki.laviebay.hkust.edu.hk/deLemus/RESEARCH_TEAMS/images/PublishedPlot/ConfirmedTable.png" alt="test for htmltag img" class="wikimg" style="display: block;width: | + | <htmltag tagname="img" src="https://wiki.laviebay.hkust.edu.hk/deLemus/RESEARCH_TEAMS/images/PublishedPlot/ConfirmedTable.png" alt="test for htmltag img" class="wikimg" style="display: block;width:35%;margin-left: auto;margin-right: auto;"></htmltag> |

==Outlined Leading Mutations== | ==Outlined Leading Mutations== | ||

Revision as of 21:41, 3 February 2023

Dynamic Expedition of Leading Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein

Spike Glycoprotein

The spike glycoprotein of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a trimeric type I viral fusion protein that binds the virus to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor of a host cell.[1] It is composed of 2 subunits: the N-terminal subunit 1 (S1) and C-terminal subunit 2 (S2), within which multiple domains lie. The S1 region facilitates ACE2 binding and is made up of an N-terminal domain (NTD ~ 1 – 325), a receptor-binding domain (RBD ~ 326 – 525), and 2 C-terminal subdomains (CTD1 and CTD2 ~ 526 – 688), while the downstream S2 region is responsible for mediating virus-host cell membrane fusion.

Update (03/02/2023)

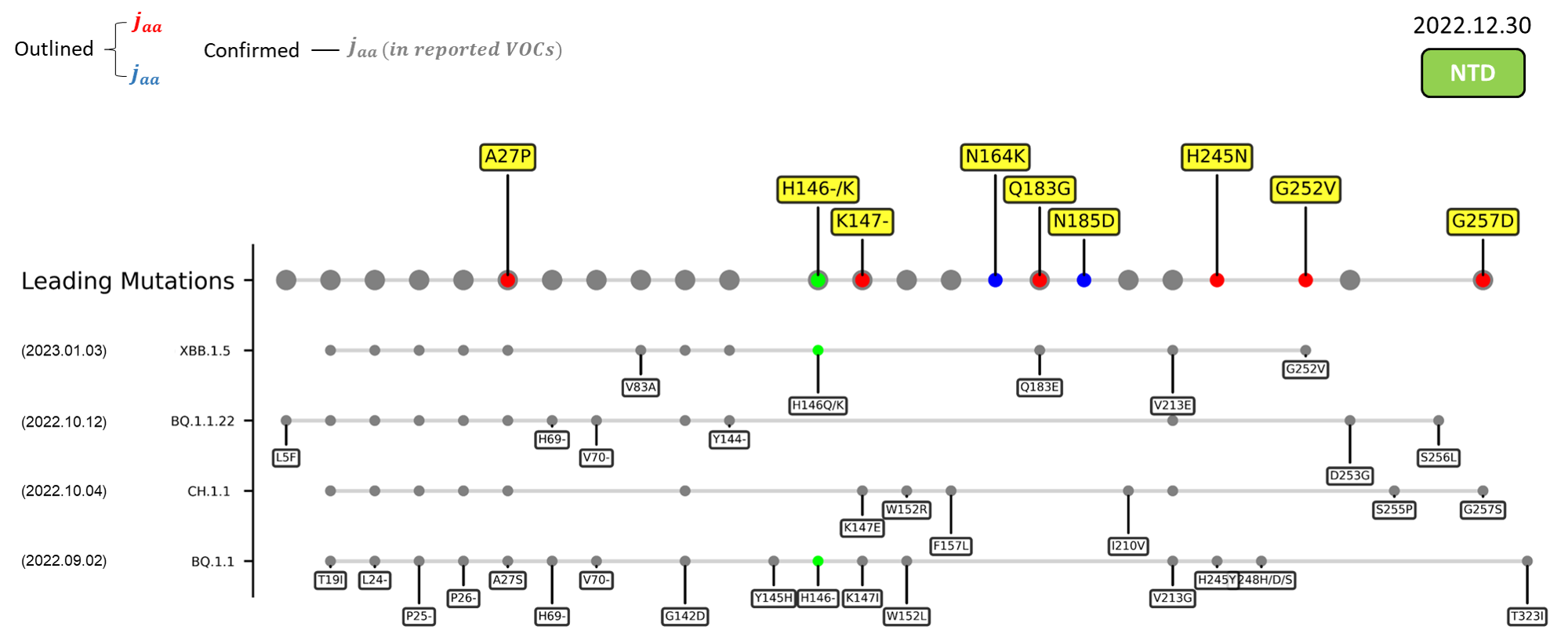

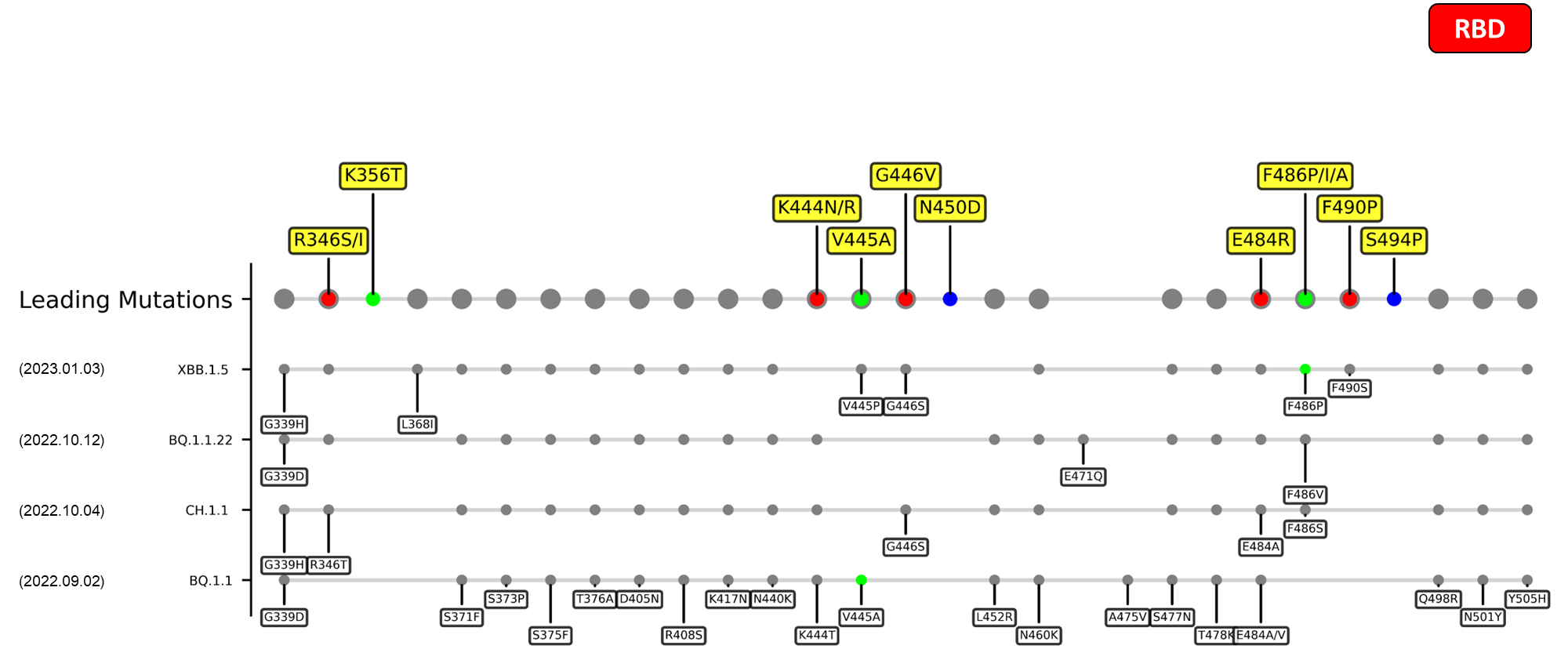

A recently discovered omicron sublineage known as XBB.1.5 has been spreading rampantly in the US since late December 2022.[2] Even though this new variant harbors only a single novel mutation, F486P, its hACE2-binding affinity has been significantly increased to a level of up to five folds when compared to its ancestor, XBB.1.[3] The figures in the sections below summarize the mutations carried by various emerging variants, juxtaposed with our detected leading mutations. As depicted, our method has successfully reported the crucial F486P mutation that defines the XBB.1.5 strain. In fact, our method has outlined this specific mutation since as early as November 2022.

Other mutations that were outlined by our deLemus analysis in December 2022, and were subsequently identified as new emerging mutations carried by the top 4 most rapidly spreading lineages according to the latest data retrieved from GISAID (2023.01.25), are listed as follows:

Outlined Leading Mutations

Based on recent report of emerging mutation from GISAID(2023.02.03), deLemus confirmed the following mutation:

V445A

The V445A mutation (BQ.1.1) outlined by our deLemus analysis is located at an RBD epitope targeted by several antibodies.[4] This mutation has been experimentally shown to not only diminish the neutralization activity of the antibody LY-CoV1404 (bebtelovimab) that is highly potent against most VOCs, including the previously circulating omicron subvariants BA.1.1.59 and BA.2, but also reduce ACE2 competition.[5]

The following leading mutations call for special attention with respect to the upcoming variants.

A27P

The A27P mutation outlined by our deLemus analysis is located at an NTD antigenic site targeted by the group 3 antibody C1717 capable of neutralizing the beta, gamma, and omicron SARS-CoV-2 variants.[6] Substitution of the A27 residue, which has been found to interact with one of C1717’s complementary-determining regions (CDR), CDRH2,[6] to proline may therefore affect the binding of this antibody.

K147-

The K147- mutation outlined by our deLemus analysis is located at the NTD. Molecular dynamics studies have shown that the K147 residue is involved in interacting with multiple monoclonal antibodies,[7] whose mutation to threonine, K147T, has been experimentally found to promote immune evasion.[8] It is therefore likely that a deletion at this position may affect the binding of antibodies, thereby reducing the neutralization susceptibility of the virus.

Q183G

The Q183G mutation outlined by our deLemus analysis is located at an NTD sialoside-binding site,[9] whose interactions with anionic glycoconjugates of the cell surface mediate the viral attachment.[10] The loss of an amide group due to the glutamine-to-glycine substitution may abrogate hydrogen bond formation between amino acid site 183 and the carboxylic group of surface sialosides,[11] thereby altering the cell entry efficiency of SARS-CoV-2.

H245N

The H245N mutation outlined by our deLemus analysis is located in the supersite loop of the NTD antigenic supersite, where 2 antibodies in particular, SLS28 and S2X333, bind.[7][8] The loss of a positive charge resulted from the replacement of a cationic histidine residue is speculated to alter the neutralization resistance of the spike glycoprotein. Furthermore, it has been noticed that the histidine-to-asparagine substitution introduces a novel NXS sequon (245NRS247), which may potentially be N-glycosylated.

G257D

The G257D mutation outlined by our deLemus analysis is located in the supersite loop of the NTD antigenic supersite, where 2 antibodies in particular, SLS28 and S2X333, bind.[7][8] The gain of a negative charge resulted from the introduction of an anionic aspartic acid residue is speculated to alter the neutralization resistance of the spike glycoprotein.

A262S

The A262S mutation outlined by our deLemus analysis is located at the NTD. This mutation has been experimentally shown to enhance the utilization of ACE2 in numerous mammals, including humans,[12] indicating that variants carrying this alanine-to-serine substitution may possess increased interspecies and intraspecies transmissibility.

R346I/S

The R346I/S mutation outlined by our deLemus analysis is located at an RBD epitome to which multiple class 3 antibodies bind.[13] Structural analyses have revealed that this arginine-to-isoleucine/serine change weakens the intermolecular interactions between amino acid 346 and several class 3 antibodies, enabling virions bearing this mutation to possess enhanced immune evasion capabilities.[14] In fact, experimental studies have demonstrated that R346S in particular can promote neutralization resistance of viruses without comprising their ACE2-binding affinity.[15][16]

N450D

The N450D mutation outlined by our deLemus analysis is located at the RBD β-sheet 1 region which has been shown to reinforce the spike-ACE2 binding in silico.[17] The possible effects of this mutation have yet to be studied, but it has been speculated that the substitution of an electrically neutral asparagine residue to an anionic aspartic acid residue may disfavor virus-receptor attachment, owing to the overall negative charge of the ACE2 binding surface.[18]

E484R/S

The E484R/S mutation outlined by our deLemus method is located within the receptor binding motif (RBM) of the RBD. Recognized by ACE2 and multiple neutralizing antibodies,[19] immense selection pressure exerted on this amino acid site has generated a high degree of polymorphism for residue 484, as seen from the fact that most SARS-CoV-2 variants carry substitutions in this site, encompassing the E484K of beta, gamma, and eta (B.1.525), E484Q of kappa (B.1.617.1), and E484A of omicron. All these mutations confer immune escape effects,[20][21][22] where the 2 former ones in particular can additionally strengthen the ACE2-binding affinity of the virus.[19] Similarly, E484R, which also replaces the initially anionic aspartic acid residue with a cationic one, has been shown to promote both immune evasion and ACE2-binding.[19] The function of E484S, on the other hand, have yet to be deduced.

D574V

The D574V mutation outlined by our deLemus analysis is located at the CTD1 region. Since the aspartic acid residue of amino acid site 574 is capable of interacting with the pH-dependent S2 refolding domain responsible for regulating RBD up-down motion, its substitution to an electrically neutral valine residue may alter the endosomal entry efficiency and immune evasion ability of SARS-CoV-2.[23]

P681Y

The P681Y mutation outlined by our deLemus analysis is located at the C-terminal of the CTD2, which contains the S1/S2 furin cleavage site (681PRRAR↓S686) important for viral transmission.[24][25] This amino acid site is particularly polymorphic, as demonstrated by the fact that multiple existing variants carry divergent mutations at this site, being the P681H of alpha and omicron and P681R of delta and kappa. Interestingly, this substitution is speculated to diminish the cleavage efficiency of the S1/S2 interface because the bulky nature of tyrosine hinders the binding of furin to the cleavage loop.[26][27]

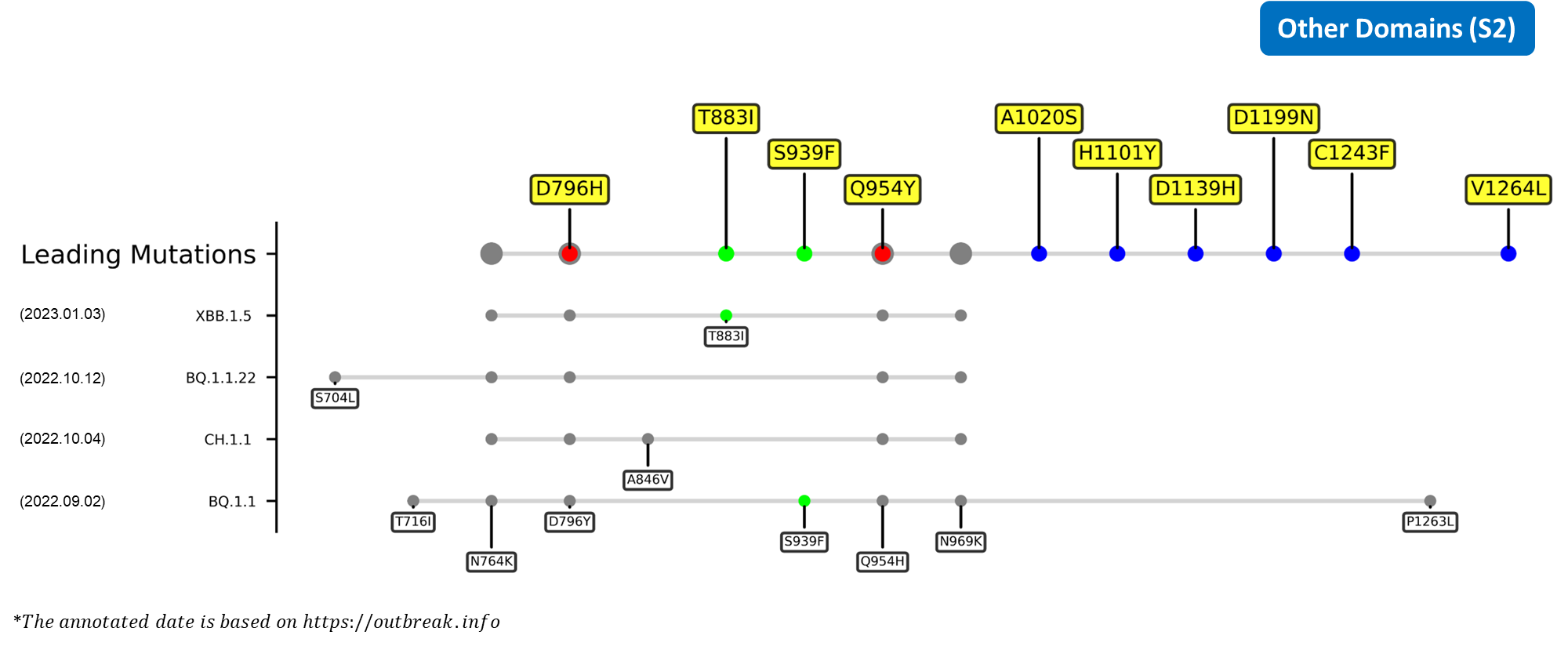

D796H

The D796H mutation outlined by our deLemus analysis is located in the S2 region. A study has shown that the administration of convalescent plasma therapy to a chronic infection patient prompted the emergence of this mutation, together with deletions spanning the NTD sites 69 and 70 (H69/V70-), within the patient's viral population.[28] The single aspartic acid-to-histidine substitution was found to enhance the neutralization resistance of the spike glycoprotein at the cost of lowering its infectivity, an undesirable effect that can be compensated by the H69/V70- double deletion.[28]

Summary

The constantly shifting epidemiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) ever since its initial outbreak has been a result of the continuous evolution of its etiological agent, SARS-CoV-2, from which numerous variants have been generated. Even within the first 2 years of this pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) has already announced 4 variants of concern (VOC), which are the previously circulating alpha (B.1.1.7), beta (B.1.351), gamma (P.1), and delta (B.1.617.2) strains, and many other variants of interest (VOI). The successive emergence of new SARS-CoV-2 variants has brought along many novel mutations, most of which continually refine and improve the fitness of the virus. For instance, these functionally advantageous mutations include the N501Y of alpha and L452R and E484Q of the B.1.617 lineage, which are capable of enhancing the ACE2-binding affinity of the spike glycoprotein.[29]

The latest SARS-CoV-2 lineage to be designated the status of VOC would be omicron (B.1.1.529) which first originated from South Africa.[30] This particular lineage alone has undergone substantial evolution over the course of its global dominance, spreading across the world like wildfire while simultaneously producing a diverse soup of dissimilar subvariants.[31] The first of its kind would be the BA.1 strain first appeared in November 2022. The supremacy of BA.1, however, would not last long, forasmuch as the emergence of the more fit BA.2 strain in December 2022 would eventually outcompete its antecedent.[32] Few months later, between March and July 2022, the successive emergences of BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5, and BA.2.75 would once again garnered the attention of the WHO and multiple countries. For one, the BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5 subvariants were found to possess enhanced antibody evasion capabilities and transmissibility when compared to the formerly active BA.2 strain,[31][33][34] allowing them to become dominant in the US and the UK.[35][36] BA.2.75, on the other hand, was the dominant variant in India, which habors higher hACE2-binding affinity than the BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants.[37][38] The complex interactions between these omicron sublineages prompted the creations of even more novel strains, including the recombinant XBB subvariant derived from BA.2.10.1 and BA.2.75 in August 2022, and the BQ.1 subvariant derived from BA.5 in October 2022. Like their predecessors, XBB swiftly rose to prominence upon its emergence, which was then succeeded by BQ.1 up till the end of 2022.[39][40] In fact, BQ.1.1, a descendent of BQ.1, was found to be the culprit behind 36.3% of the total US reported COVID-19 cases in December 2022.[41]

Recent emerging variant (EV) data retrieved from GISAID, as of 17 January 2023, has revealed that the top 4 most rapidly spreading lineages are the BA.1.1.22, CH.1.1, XBB.1.5, and BQ.1.1 variants, among which XBB.1.5 has been found to be especially prevalent in the US, making up of more than 40% of its sequence coverage in early January 2023.[41] The identified leading mutations are listed as follows:

NTD

RBD

CTDs

S2

References

- ↑ Jackson, C. B., Farzan, M., Chen, B. & Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 23, 3–20 (2021).

- ↑ COVID Data Tracker: Variant Proportion https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#variant-proportions (2023).

- ↑ Yue, C. et al. Enhanced transmissibility of XBB.1.5 is contributed by both strong ACE2 binding and antibody evasion. Preprint at https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.01.03.522427v2 (2023).

- ↑ Weisblum, Y. et al. Escape from neutralizing antibodies by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants. eLife 9, (2020).

- ↑ Westendorf, K. et al. LY-CoV1404 (bebtelovimab) potently neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 variants. Cell Rep 39, 110812 (2022).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Li, B. et al. Identification of Potential Binding Sites of Sialic Acids on the RBD Domain of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Front Chem. 9, 659764 (2021)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Zhou, L, et al. Predicting Spike Protein NTD Mutations of SARS-CoV-2 Causing Immune Evasion by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Phys Chem Chem Phys 24, 3410–3419 (2022).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 McCallum, M. et al. N-Terminal Domain Antigenic Mapping Reveals a Site of Vulnerability for SARS-CoV-2. Cell 184, 2332-2347 (2021).

- ↑ Guo, H. et al. The Glycan-Binding Trait of the Sarbecovirus Spike N-Terminal Domain Reveals an Evolutionary Footprint. J Virol. 96, e00958-22 (2022)

- ↑ Sun, X.-L. The role of cell surface sialic acids for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Glycobiology 31, 1245–1253 (2021).

- ↑ Buchanan, C. J. et al. Pathogen-sugar interactions revealed by Universal Saturation Transfer Analysis. Science 377, (2022).

- ↑ Wang, Q. et al. Key Mutations on Spike Protein Altering ACE2 Receptor Utilization and Potentially Expanding Host Range of Emerging SARS‐CoV‐2 Variants. J Med Virol. 95, 1-11 (2022).

- ↑ Gaebler, C. et al. Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nature 591, 639–644 (2021).

- ↑ Wang, Q. et al. Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariant BA.4.6 to antibody neutralisation. Lancet Infect Dis 22, 1666–1668 (2022).

- ↑ Yi, C. et al. Comprehensive mapping of binding hot spots of SARS-CoV-2 RBD-specific neutralizing antibodies for tracking immune escape variants. Genome Med 13, (2021).

- ↑ Magnus, C. L. et al. Targeted escape of SARS-CoV-2 in vitro from monoclonal antibody S309, the precursor of sotrovimab. Front Immunol 13, (2022).

- ↑ Cong, Y. et al. Anchor-locker binding mechanism of the coronavirus spike protein to human ACE2: Insights from computational analysis. J Chem Inf Model 61, 3529–3542 (2021).

- ↑ Xie, Y. et al. Spike proteins of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2 utilize different mechanisms to bind with human ACE2. Front Mol Biosci 7, (2020).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Gan, H. H., Twaddle, A., Marchand, B. & Gunsalus, K. C. Structural modeling of the SARS-CoV-2 spike/human ACE2 complex interface can identify high-affinity variants associated with increased transmissibility. J Mol Biol 433, 167051 (2021).

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:0 - ↑ Liu, Z. et al. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations that attenuate monoclonal and serum antibody neutralization. Cell Host Microbe 29, (2021).

- ↑ VanBlargan, L. A. et al. An infectious SARS-CoV-2 B.1.1.529 omicron virus escapes neutralization by therapeutic monoclonal antibodies. Nat Med 28, 490–495 (2022).

- ↑ Zhou, T. et al. Cryo-EM structures of SARS-CoV-2 spike without and with ACE2 reveal a pH-dependent switch to mediate endosomal positioning of receptor-binding domains. Cell Host Microbe 28, (2020).

- ↑ Jaimes, J. A., Millet, J. K. & Whittaker, G. R. Proteolytic cleavage of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and the role of the novel S1/S2 Site. iScience 23, 101212 (2020).

- ↑ Hoffmann, M., Kleine-Weber, H. & Pöhlmann, S. A multibasic cleavage site in the spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 is essential for infection of human lung cells. Mol Cell 78, (2020).

- ↑ Henrich, S. et al. The crystal structure of the proprotein processing proteinase furin explains its stringent specificity. Nat Struct Mol Biol 10, 520–526 (2003).

- ↑ Tian, S. A 20 residues motif delineates the furin cleavage site and its physical properties may influence viral fusion. Biochem Insights 2, (2009).

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Kemp, S. A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution during treatment of chronic infection. Nature 592, 277–282 (2021).

- ↑ Aggarwal, A. et al. Mechanistic Insights into the Effects of Key Mutations on SARS-CoV-2 RBD–ACE2 Binding. Phys Chem Chem Phys 23, 26451–26458 (2021)

- ↑ Karim, S. S. A. & Karim, Q. A. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: A new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398, 2126–2128 (2021).

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Tegally, H. et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 omicron lineages BA.4 and BA.5 in South Africa. Nat Med 28, 1785–1790 (2022).

- ↑ Yamasoba, D. et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2 spike. Cell 185, 2103-2115.e19 (2022).

- ↑ Cao, Y. et al. BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 escape antibodies elicited by Omicron Infection. Nature 608, 593–602 (2022).

- ↑ Wang, Q. et al. Antibody evasion by SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5. Nature 608, 603–608 (2022).

- ↑ Callaway, E. What Omicron’s BA.4 and BA.5 variants mean for the pandemic. Nature 606, 848–849 (2022).

- ↑ Del Rio, C. & Malani, P. N. COVID-19 in 2022 - The Beginning of the End or the End of the Beginning? JAMA 327, 2389–2390 (2022).

- ↑ Cao, Y. et al. Characterization of the enhanced infectivity and antibody evasion of Omicron BA.2.75. Cell Host Microbe 30, (2022).

- ↑ Shaheen, N. et al. Could the New BA.2.75 Sub-Variant Cause the Emergence of a Global Epidemic of COVID-19? A Scoping Review. Infect Drug Resist 15, 6317–6330 (2022).

- ↑ Wang, Q. et al. Alarming antibody evasion properties of rising SARS-CoV-2 BQ and XBB subvariants. Cell 186, (2023).

- ↑ European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Spread of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant sub-lineage BQ.1 in the EU/EEA https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Epi-update-BQ1.pdf (2022).

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Highly immune evasive omicron XBB.1.5 variant is quickly becoming dominant in U.S. as it doubles weekly https://www.cnbc.com/2022/12/30/covid-news-omicron-xbbpoint1point5-is-highly-immune-evasive-and-binds-better-to-cells.html (2023).

Cite error: <ref> tag with name "LiImpactCell" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.

Cite error: <ref> tag with name "Olivie" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.