deLemus

Dynamic Expedition of Leading Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoproteins

The dynamic epidemiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) since its outbreak has been a result of the continuous evolution of its etiological agent, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Within the first 2 years of this pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) has already announced 4 variants of concern (VOC), namely alpha (B.1.1.7), beta (B.1.351), gamma (P.1), and delta (B.1.617.2), together with numerous variants of interest (VOI). The latest lineage to be designated a VOC would be omicron (B.1.1.529),[1] from which a diverse variant soup is generated.[2] From the original BA.1 strain of November 2021 to the most recent XBB and BQ.1 strains of late 2022,[3][4] each omicron subvariant has successively proliferated and outcompeted its once dominant antecedent.[5] The emergence of all these variants has brought along many novel mutations that continue to fine-tune the fitness of the virus,[6][7] leading to its persistent global circulation. Recent emerging variant (EV) data retrieved from GISAID, as of 17 January 2023, has revealed that the top 4 most rapidly spreading lineages are the BA.1.1.22, CH.1.1, XBB.1.5, and BQ.1.1 variants, among which XBB.1.5 has been found to be especially prevalent in the US,[8] making up of more than 40% of its sequence coverage in early January 2023.

Spike Glycoprotein

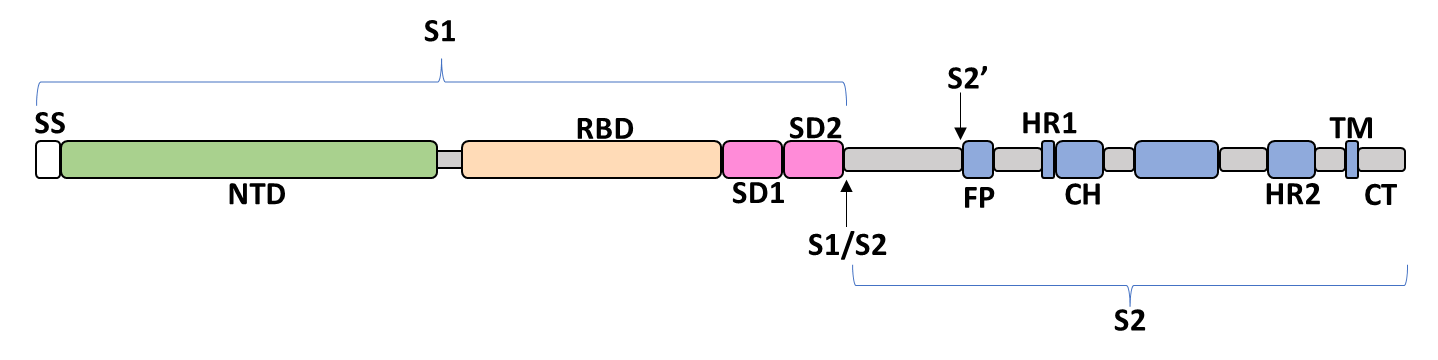

The spike glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2 is a trimeric type I viral fusion protein that binds the virus to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor of a host cell.[9] It is composed of 2 subunits: the N-terminal subunit 1 (S1) and C-terminal subunit 2 (S2), within which multiple domains lie. The S1 region facilitates ACE2 binding and is made up of an N-terminal domain (NTD ~ 1 – 325), a receptor-binding domain (RBD ~ 326 – 525), and 2 C-terminal subdomains (CTD1 and CTD2 ~ 526 – 688), while the downstream S2 region is responsible for mediating virus-host cell membrane fusion.

Update

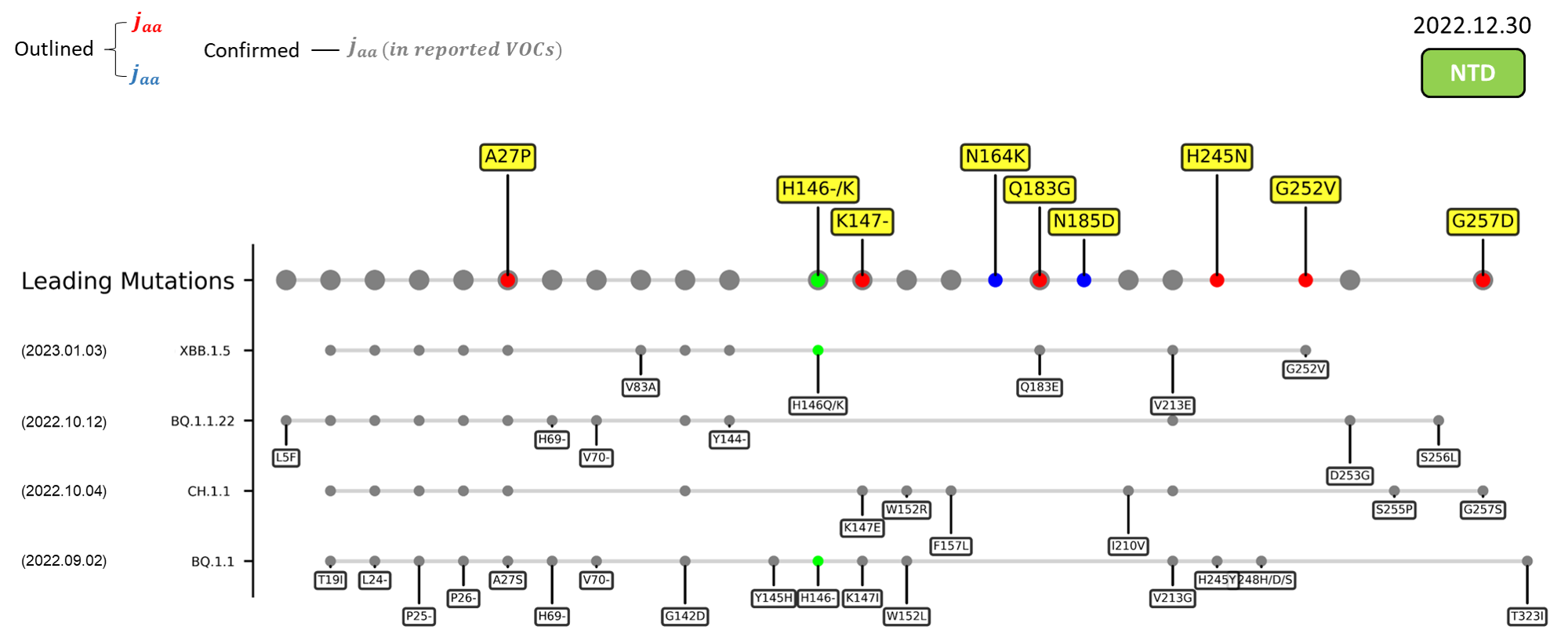

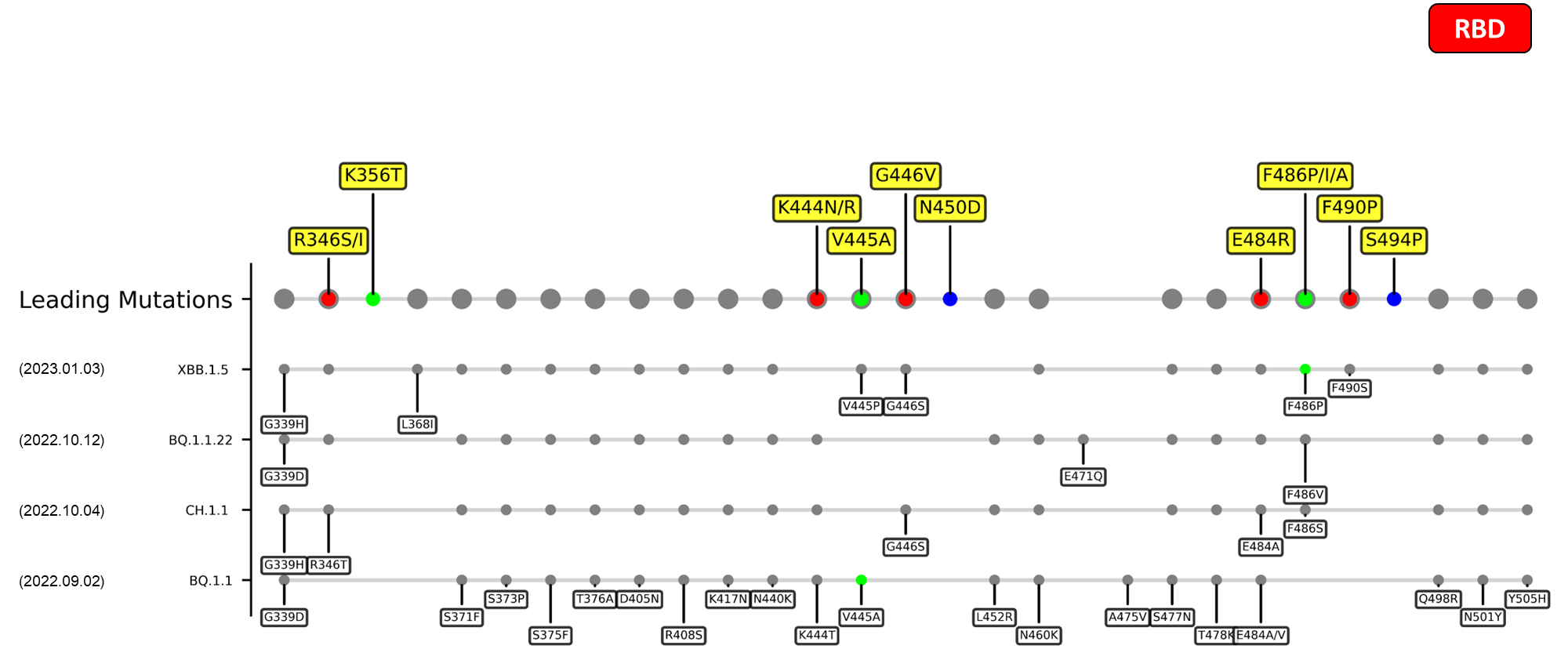

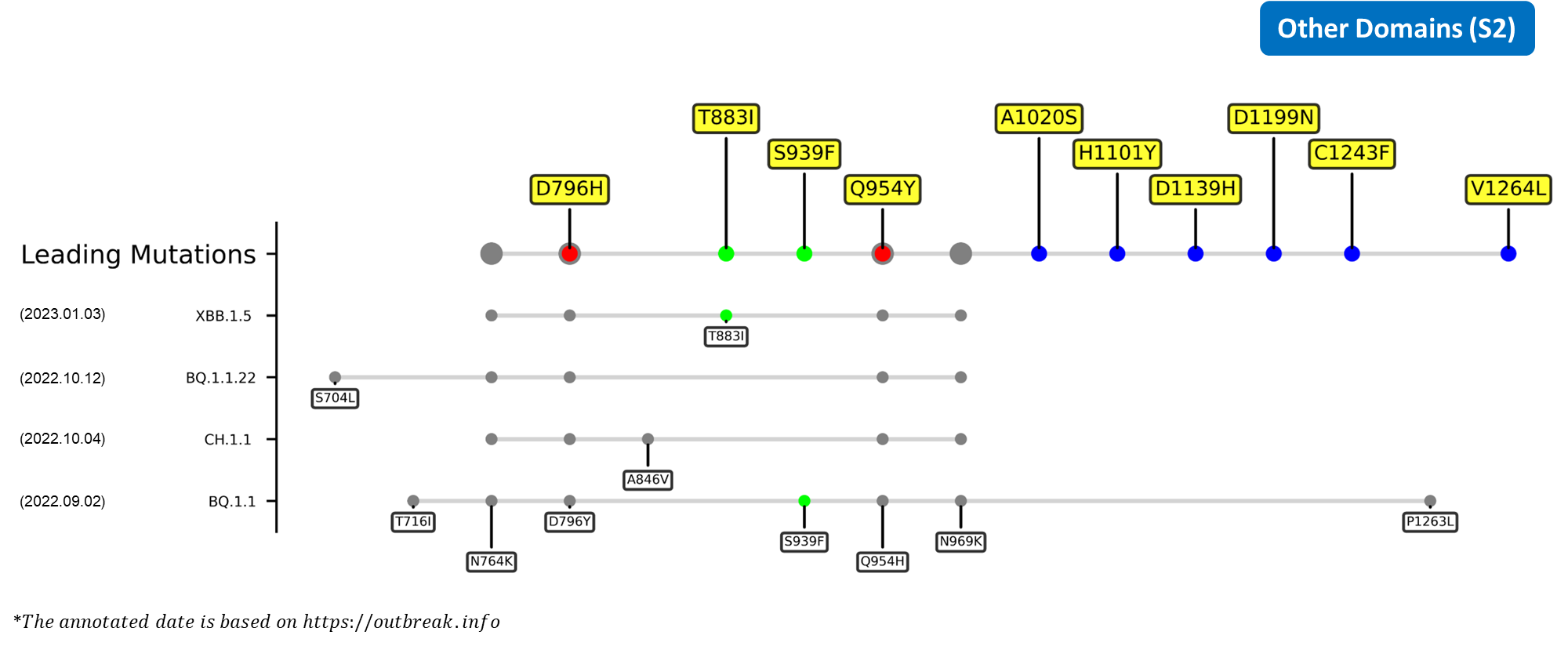

The identified leading mutations in 2023 are listed as follows [10]:

- Generated 3D structure of spike protein with highlighted leading mutations (AlphaFold2, colab version 2022).

Here are the recently confirmed leading mutations.

2023.01.31

| Outlined Mutations | Confirmed in VOC/Emerging Variants |

|---|---|

| V445A | BQ.1.1 |

| T883I | BQ.1.1 |

2023.01.17 - 2023.01.25

| Outlined Mutations | Confirmed in VOC/Emerging Variants |

|---|---|

| H146- / H146K | BQ.1.1 / XBB.1.5 |

| F486A | BQ.1.1 |

| E583D | BQ.1.1 |

| Q613H | BQ.1.1 |

| S939F | BQ.1.1 |

*The reported emerging mutations are provided by GISAIDCite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

|-

|G257D

|Located in the supersite loop of the NTD antigenic supersite for antibodies SLS28 and S2X333[11][12] ; Caused a gain of negative charge

|-

|A262S

|Enhance the utilization of ACE2 in numerous mammals[13] ; May increase interspecies and intraspecies transmissibility

|}

RBD

| Outlined Mutations | Conformation |

|---|---|

| R346I/S | Possibly lead to immune evasion due to the disruption of class 3 antibodies binding site[14] [15] |

| K444N/R | Escape mutations for covalescent plasma[16] |

| G446V | Substantially decreases the neutralization titers of plasma[17] |

| N450D | Results in antibody resistance[18] |

| E484R/S | A site of mutation being reported in multiple variants, mutation at this site could harbor escape mutations that impede the binding and neutralization ability of antibodies[19] [17] |

| F490P | Mutation at this site enables antibody escape over mAb COV2-2479, COV2-2050, COV2-2096 based on DMS study.[17] |

| S494P | This mutation persistently shows up in an immunocompromised patient of COVID-19, which was treated various drugs and antibodies e.g. remdesivir, intravenous immunoglobulin, etc.[20] |

CTDs

| Outlined Mutations | Conformation |

|---|---|

| T547I | Functional impact to be confirmed in future investigation. |

| T572I | Functional impact to be confirmed in future investigation. |

| D574V | Located at the CTD1 region, substitution to an electrically neutral valine residue permits the endosomal entry efficiency and immune evasion ability of SARS-CoV-2.[21] |

| E619Q | Functional impact to be confirmed in future investigation. |

| E658S | Functional impact to be confirmed in future investigation. |

| I666V | Functional impact to be confirmed in future investigation. |

| S673G | Functional impact to be confirmed in future investigation. |

| P681Y | Located at the C-terminal of the CTD2, this substitution can diminish the cleavage efficiency of the S1/S2 interface because the bulky nature of tyrosine hinders the binding of furin to the cleavage loop.[22][23] |

| I688V | Functional impact to be confirmed in future investigation. |

S2

| Outlined Mutations | Conformation |

|---|---|

| D796H | Located in S2 region, the single aspartic acid-to-histidine substitution was found to enhance the neutralization resistance of the spike glycoprotein in a chronical infection patient.[24] |

-->

References

- ↑ Karim, S. S. A. & Karim, Q. A. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: A new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398, 2126 (2021).

- ↑ Callaway, E. COVID ‘variant soup’ is making winter surges hard to predict. Nature 611, 213 (2022).

- ↑ Wang, Q. et al. Alarming antibody evasion properties of rising SARS-CoV-2 BQ and XBB subvariants. Cell 186, 279 (2023).

- ↑ Qu, P. et al. Enhanced Neutralization Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Subvariants BQ.1, BQ.1.1, BA.4.6, BF.7, and BA.2.75.2. Cell Host Microbe 31, 9 (2023)

- ↑ Rössler, A. et al. BA.2 and BA.5 Omicron Differ Immunologically from Both BA.1 Omicron and Pre-Omicron Variants. Nat Commun 13, 7701 (2022)

- ↑ Carabelli, A. M. et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: Immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat Rev Microbiol (2023). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-022-00841-7.

- ↑ Witte, L. et al. Epistasis lowers the genetic barrier to SARS-CoV-2 neutralizing antibody escape. Nat Commun 14, 302 (2023).

- ↑ Callaway, E. Coronavirus variant XBB.1.5 rises in the United States — is it a global threat? Nature 613, 222 (2023).

- ↑ Jackson, C. B., Farzan, M., Chen, B. & Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 23, 3 (2021).

- ↑ deLemus team, Analysis of Leading Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoproteins (in preparation, 2023).

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:4 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:3 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWang_JMedVirol2022 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGaebler - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWangQ_LancetID2022 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWeisblum_eLife - ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGreaney - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCong_CellHM2021 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:0 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedChoi - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedZhou_CellHM2020 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHenrich - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedTian_2009 - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedKempCIP

Cite error: <ref> tag with name "GISAID" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.