deLemus

Dynamic Expedition of Leading Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Spike Glycoprotein

Spike Glycoprotein

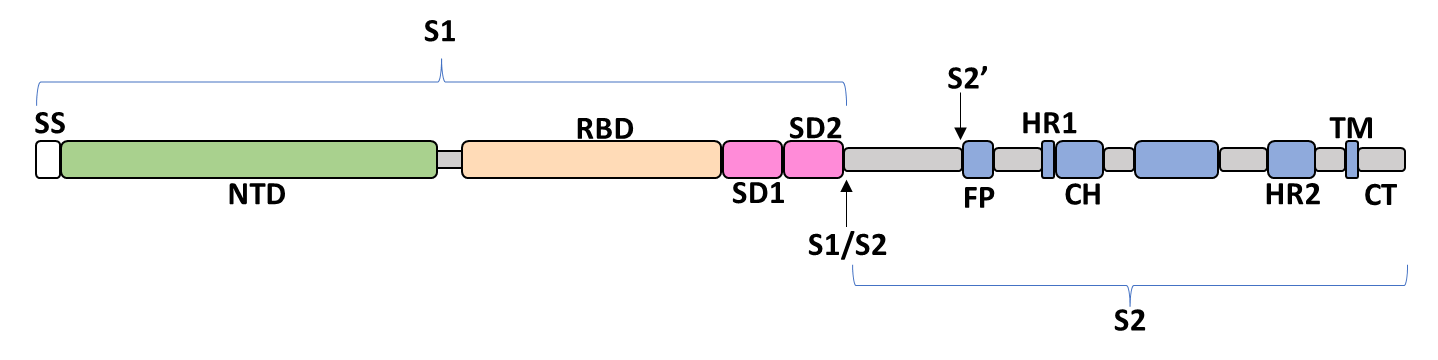

The spike glycoprotein of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a trimeric type I viral fusion protein that binds the virus to the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor of a host cell.[1] It is composed of 2 subunits: the N-terminal subunit 1 (S1) and C-terminal subunit 2 (S2), within which multiple domains lie. The S1 region facilitates ACE2 binding and is made up of an N-terminal domain (NTD ~ 1 – 325), a receptor-binding domain (RBD ~ 326 – 525), and 2 C-terminal subdomains (CTD1 and CTD2 ~ 526 – 688), while the downstream S2 region is responsible for mediating virus-host cell membrane fusion.

Update (03/02/2023)

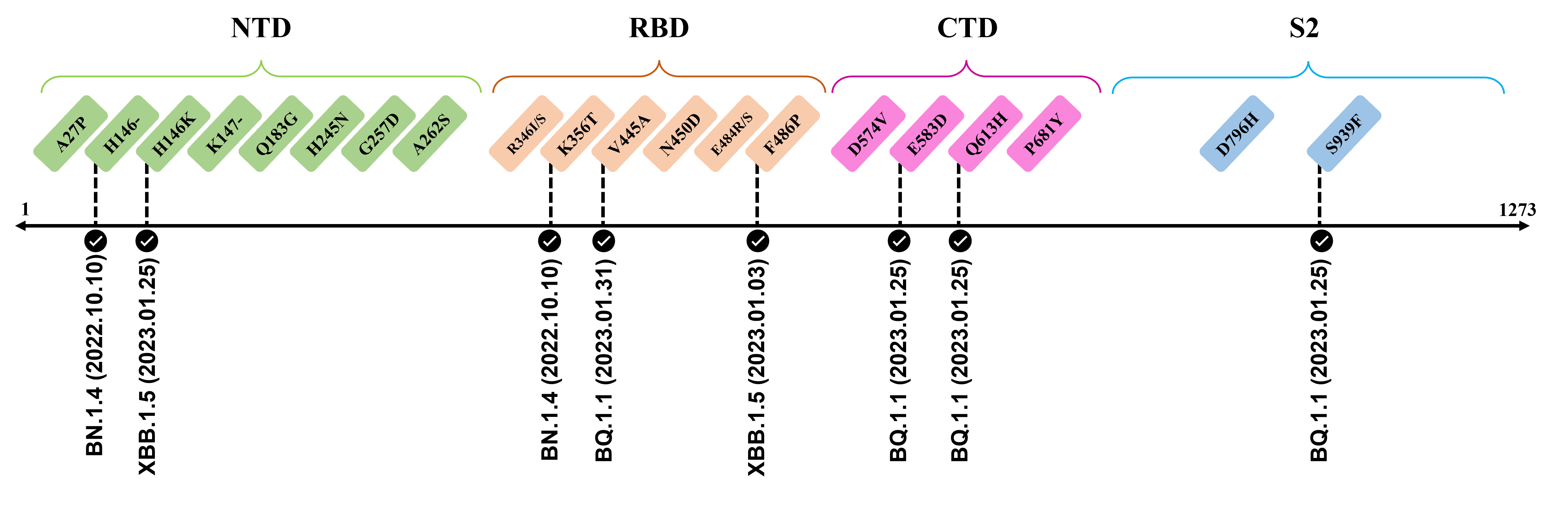

The recently confirmed leading mutations are listed as follows.

2023.01.31

| Mutation | Information |

|---|---|

| V445A | Confirmed in BQ.1.1 ; Amino acid site located at an RBD epitope[2] ; Mutation reduces neutralization by antibody [3] |

2023.01.17 - 2023.01.25

| Mutation | Information |

|---|---|

| H146-/K | Reported in BQ.1.1 and XBB.1.5 ; Amino acid site recognized by mAbs targeting NTD[4] |

| E583D | Shows up in BQ.1.1 ; Viral functions to be confirmed by further investigation |

| Q613H | Emerge in BQ.1.1 ; Speculate to enhance replicative fitness and transmissibility due to close proximity to D614G ; Potential functions to be elucidated[5][6] |

| S939F | Observed in BQ.1.1 ; Destabilize both pre-fusion and post-fusion S2 conformation[7] ; Capable to enhance infectivity and modulate T-cell immune response when combined with D614G[8][9] |

The following leading mutations call for special attention with respect to the upcoming variants.

NTD

| Mutation | Information |

|---|---|

| A27P | An antigenic site targeted by the group 3 antibody C1717[10] |

| K147- | Involved in interacting with multiple monoclonal antibodies[11] ; Mutation to threonine (K147T) at this site promotes immune evasion[4] |

| N164K | Functional impact to be confirmed in future investigation. |

| Q183G | Interactions with surface glycoconjugates mediate the viral attachment[12] ; Caused a loss of an amide group; May abrogate the hydrogen bond between the amino acid and the carboxylic group of surface sialosides[13] |

| N185D | Functional impact to be confirmed in future investigation. |

| H245N | Located in the supersite loop of the NTD antigenic supersite for antibodies SLS28 and S2X333[11][4] ; Caused a loss of a positive charge ; Introduces an NXS sequon (245NRS247) for N-glycosylation |

| G252V | Site is critical for the binding of human antibody COV2-3439[14] |

| G257D | Located in the supersite loop of the NTD antigenic supersite for antibodies SLS28 and S2X333[11][4] ; Caused a gain of negative charge |

| A262S | Enhance the utilization of ACE2 in numerous mammals[15] ; May increase interspecies and intraspecies transmissibility |

RBD

| Mutation | Information |

|---|---|

| R346I/S | Possibly lead to immune evasion due to the disruption of class 3 antibodies binding site[16] [17] |

| K444N/R | Escape mutations for covalescent plasmaCite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

[10] [4] [11] [18] [6] [13] [19] [20] [21] [3] [22] [23] [24] [9] [25] [16] [26] [27] [1] [28] [29] [8] [7] [30] [12] [31] [32] [33] [15] [17] [34] [2] [35] [36] [37] </references> Structure Testing

|

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Jackson, C. B., Farzan, M., Chen, B. & Choe, H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 23, 3–20 (2021).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Weisblum, Y. et al. Escape from neutralizing antibodies by SARS-CoV-2 spike protein variants. eLife 9, (2020).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Westendorf, K. et al. LY-CoV1404 (bebtelovimab) potently neutralizes SARS-CoV-2 variants. Cell Rep 39, 110812 (2022).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 McCallum, M. et al. N-Terminal Domain Antigenic Mapping Reveals a Site of Vulnerability for SARS-CoV-2. Cell 184, 2332-2347 (2021).

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs named:0 - ↑ 6.0 6.1 Bugembe, D. L. et al. Emergence and spread of a SARS-COV-2 lineage a variant (A.23.1) with altered Spike Protein in Uganda. Nat Microbiol 6, 1094–1101 (2021).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Oliva, R., Shaikh, A. R., Petta, A., Vangone, A. & Cavallo, L. D936Y and other mutations in the fusion core of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein heptad repeat 1: Frequency, geographical distribution, and structural effect. Molecules 26, 1–13 (2021).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Li, Q. et al. The Impact of Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 Spike on Viral Infectivity and Antigenicity. Cell 182, 1284-1294.e9 (2020).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Donzelli, S. et al. Evidence of a SARS-CoV-2 double spike mutation D614G/S939F potentially affecting immune response of infected subjects. Comput Struct Biotechnol J 20, 733–744 (2022).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Li, B. et al. Identification of Potential Binding Sites of Sialic Acids on the RBD Domain of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Front Chem. 9, 659764 (2021)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Zhou, L, et al. Predicting Spike Protein NTD Mutations of SARS-CoV-2 Causing Immune Evasion by Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Phys Chem Chem Phys 24, 3410–3419 (2022).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Sun, X.-L. The role of cell surface sialic acids for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Glycobiology 31, 1245–1253 (2021).

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Buchanan, C. J. et al. Pathogen-sugar interactions revealed by Universal Saturation Transfer Analysis. Science 377, (2022).

- ↑ Suryadevara N. et al. An antibody targeting the N-terminal domain of SARS-CoV-2 disrupts the spike trimer. J Clin Invest 132, 159062 (2022).

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Wang, Q. et al. Key Mutations on Spike Protein Altering ACE2 Receptor Utilization and Potentially Expanding Host Range of Emerging SARS‐CoV‐2 Variants. J Med Virol. 95, 1-11 (2022).

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Gaebler, C. et al. Evolution of antibody immunity to SARS-CoV-2. Nature 591, 639–644 (2021).

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Wang, Q. et al. Resistance of SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariant BA.4.6 to antibody neutralisation. Lancet Infect Dis 22, 1666–1668 (2022).

- ↑ Aggarwal, A. et al. Mechanistic Insights into the Effects of Key Mutations on SARS-CoV-2 RBD–ACE2 Binding. Phys Chem Chem Phys 23, 26451–26458 (2021)

- ↑ Callaway, E. What Omicron’s BA.4 and BA.5 variants mean for the pandemic. Nature 606, 848–849 (2022).

- ↑ Cao, Y. et al. Characterization of the enhanced infectivity and antibody evasion of Omicron BA.2.75. Cell Host Microbe 30, (2022).

- ↑ Cao, Y. et al. BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5 escape antibodies elicited by Omicron Infection. Nature 608, 593–602 (2022).

- ↑ Highly immune evasive omicron XBB.1.5 variant is quickly becoming dominant in U.S. as it doubles weekly https://www.cnbc.com/2022/12/30/covid-news-omicron-xbbpoint1point5-is-highly-immune-evasive-and-binds-better-to-cells.html (2023).

- ↑ Cong, Z. et al. Identification of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutations that attenuate monoclonal and serum antibody neutralization. Cell Host & Microbe 29, 1931-3128 (2021).

- ↑ Del Rio, C. & Malani, P. N. COVID-19 in 2022 - The Beginning of the End or the End of the Beginning? JAMA 327, 2389–2390 (2022).

- ↑ European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control: Spread of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant sub-lineage BQ.1 in the EU/EEA https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/Epi-update-BQ1.pdf (2022).

- ↑ Greaney, A. et al. Comprehensive mapping of mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 receptor-binding domain that affect recognition by polyclonal human plasma antibodies. Cell Host Microbe 29, 463-476 (2021).

- ↑ Henrich, S. et al. The crystal structure of the proprotein processing proteinase furin explains its stringent specificity. Nat Struct Mol Biol 10, 520–526 (2003).

- ↑ Karim, S. S. A. & Karim, Q. A. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 variant: A new chapter in the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet 398, 2126–2128 (2021).

- ↑ Kemp, S. A. et al. SARS-CoV-2 evolution during treatment of chronic infection. Nature 592, 277–282 (2021).

- ↑ Shaheen, N. et al. Could the New BA.2.75 Sub-Variant Cause the Emergence of a Global Epidemic of COVID-19? A Scoping Review. Infect Drug Resist 15, 6317–6330 (2022).

- ↑ Tian, S. A 20 residues motif delineates the furin cleavage site and its physical properties may influence viral fusion. Biochem Insights 2, (2009).

- ↑ Tegally, H. et al. Emergence of SARS-CoV-2 omicron lineages BA.4 and BA.5 in South Africa. Nat Med 28, 1785–1790 (2022).

- ↑ Wang, Q. et al. Alarming antibody evasion properties of rising SARS-CoV-2 BQ and XBB subvariants. Cell 186, (2023).

- ↑ Wang, Q. et al. Antibody evasion by SARS-CoV-2 omicron subvariants BA.2.12.1, BA.4 and BA.5. Nature 608, 603–608 (2022).

- ↑ Yamasoba, D. et al. Virological characteristics of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2 spike. Cell 185, 2103-2115.e19 (2022).

- ↑ Zhou, T. et al. Cryo-EM structures of SARS-CoV-2 spike without and with ACE2 reveal a pH-dependent switch to mediate endosomal positioning of receptor-binding domains. Cell Host Microbe 28, (2020).

- ↑ Choi, Bina and Choudhary, Manish C. and Regan, James and Sparks, Jeffrey A. and Padera, Robert F. and Qiu, Xueting and Solomon, Isaac H. and Kuo, Hsiao-Hsuan and Boucau, Julie and Bowman, Kathryn and Adhikari, U. Das and Winkler, Marisa L. and Mueller, Al, J. Z. Persistence and Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 in an Immunocompromised Host. new engl J. Med. February, 2008–2009 (2020).